Identifying Trends in Firearm Suicide Among American Indian and Alaska Native Young Men, 1999–2020

American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) young men consistently have the highest suicide rates. In 2021, among AIAN men aged 20–29 years, the suicide rate was 92.36 per 100000 (1), a stark contrast to the national average of 31.27 per 100,000 (1) among all other men of the same age. Nationally, firearms are the most common and most lethal method of suicide. Among AIAN men aged 20–29 years, the firearm suicide rate was 34.38 per 100,000 (1) compared to 18.25 per 100,000 nationally in 2021 (1).

Despite the ongoing mental health crisis impacting young AIAN men, research on firearm suicide in this group is startlingly sparse. How firearm suicide rates have changed over time in this population has not been established. Mental health disparities among AIANs are related to the ongoing impact of historical trauma and structural violence—including significant challenges posed by mental health services, which is the delivery location for many firearm suicide interventions (2, 3). Considering the need for research on firearm suicide among young AIAN men, we evaluated long‐term trends in firearm suicide rates.

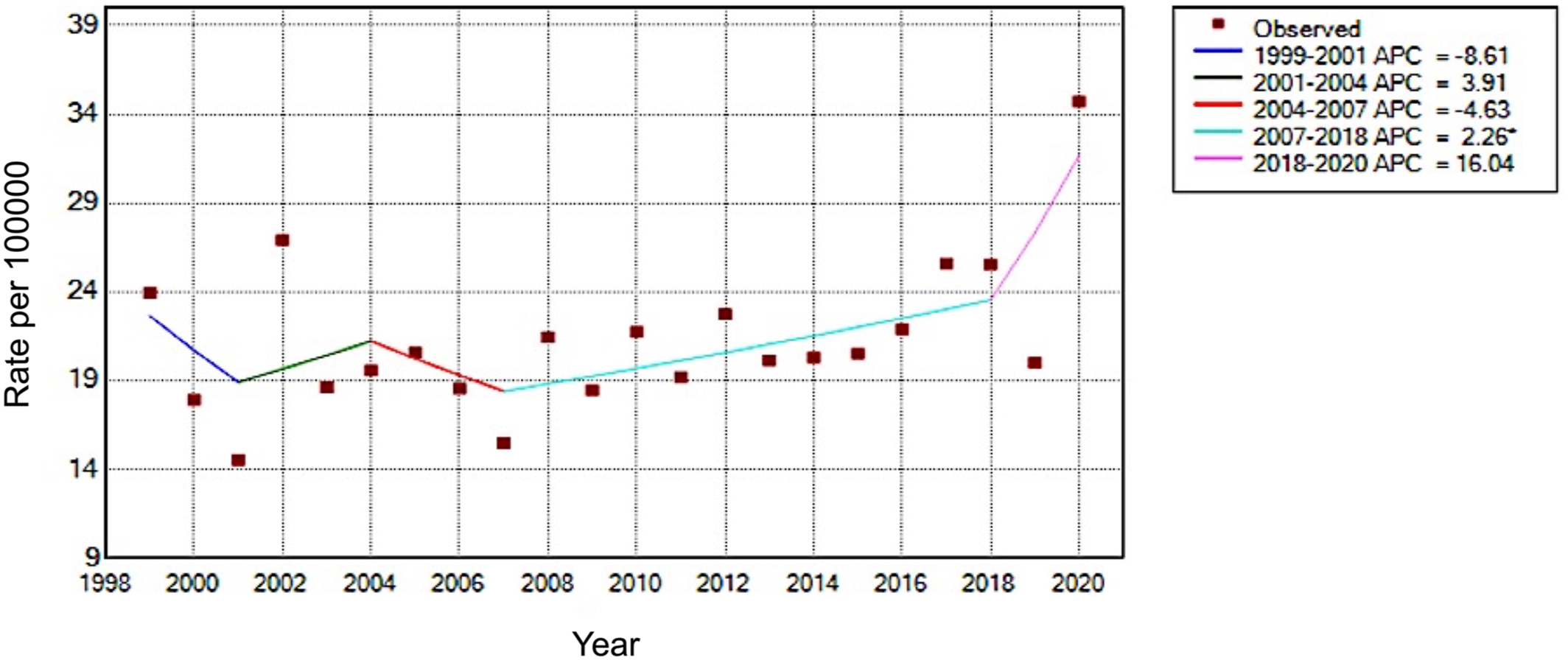

Using mortality data on all non‐Hispanic AIAN men ages 18–29 years who died by firearm suicide (ICD‐10 Codes: X72‐X74) from years 1999 to 2020 (1), we estimated temporal trends in annual crude mortality rates per 100,000 (Figure 1). Overall, the firearm suicide rate per 100,000 increased from 23.94 in 1999 to 34.72 in 2020, with a significant annual percent change (APC) of 1.47% (95%CI, 0.2%–2.7%). However, the trend for all data years does not accurately describe temporal changes. Rate changes remained statistically stable between 1999 and 2006 but significantly increased from 2007 to 2018 (APC = 2.26%; 95%CI, 0.1%–4.5%). The most recent trend period identified was from 2018 to 2020. During this time, the change in trend was not statistically significant (APC = 16.04%; 95%CI, −9.7% to 49.2%). Alarmingly, the observed firearm suicide rate increased by 14.73 per 100,000 (71.6%) in the single year from 2019 to 2020.

FIGURE 1. Jointpoint regression on firearm suicide rates among American Indian and Alaska Native males ages 18–29 years with annual percent change (APC) estimates identifying trend periods from 1999 through 2020.

AIAN young men have a recognized high vulnerability to firearm suicide, which is increasing since 1999. Some significant barriers to addressing this crisis include high rates of uninsured, lack of tailored mental health services, and the unique challenges posed by implementing firearm means restriction interventions in indigenous cultural contexts (2, 3, 4). Considering persistently high suicide rates, standard clinical measures may be insufficient to measure suicide risk among AIANs. This supports the long‐standing community‐based push for mental health services tailored to AIAN‐specific needs, including those related to substance use. There is a lethal interaction between alcohol intoxication and firearm suicide. Notably, alcohol involvement in firearm suicides is exceptionally high among young AIAN men (63% versus 42% of their same‐age counterparts of other races) (5), which could pose important clinical considerations for attenuating risk in this population.

Clinicians and researchers need to be aware of the high and increasing burden of firearm suicide among young AIAN men. Collaborative work with AIAN communities is needed to develop appropriate programs to address risk and promote resilience. If designed appropriately to reach this at‐risk community, broad‐reaching programs such as lethal means restriction (e.g., firearm safe storage) initiatives and culturally appropriate mental health services hold promise.

1

2

3

4

5